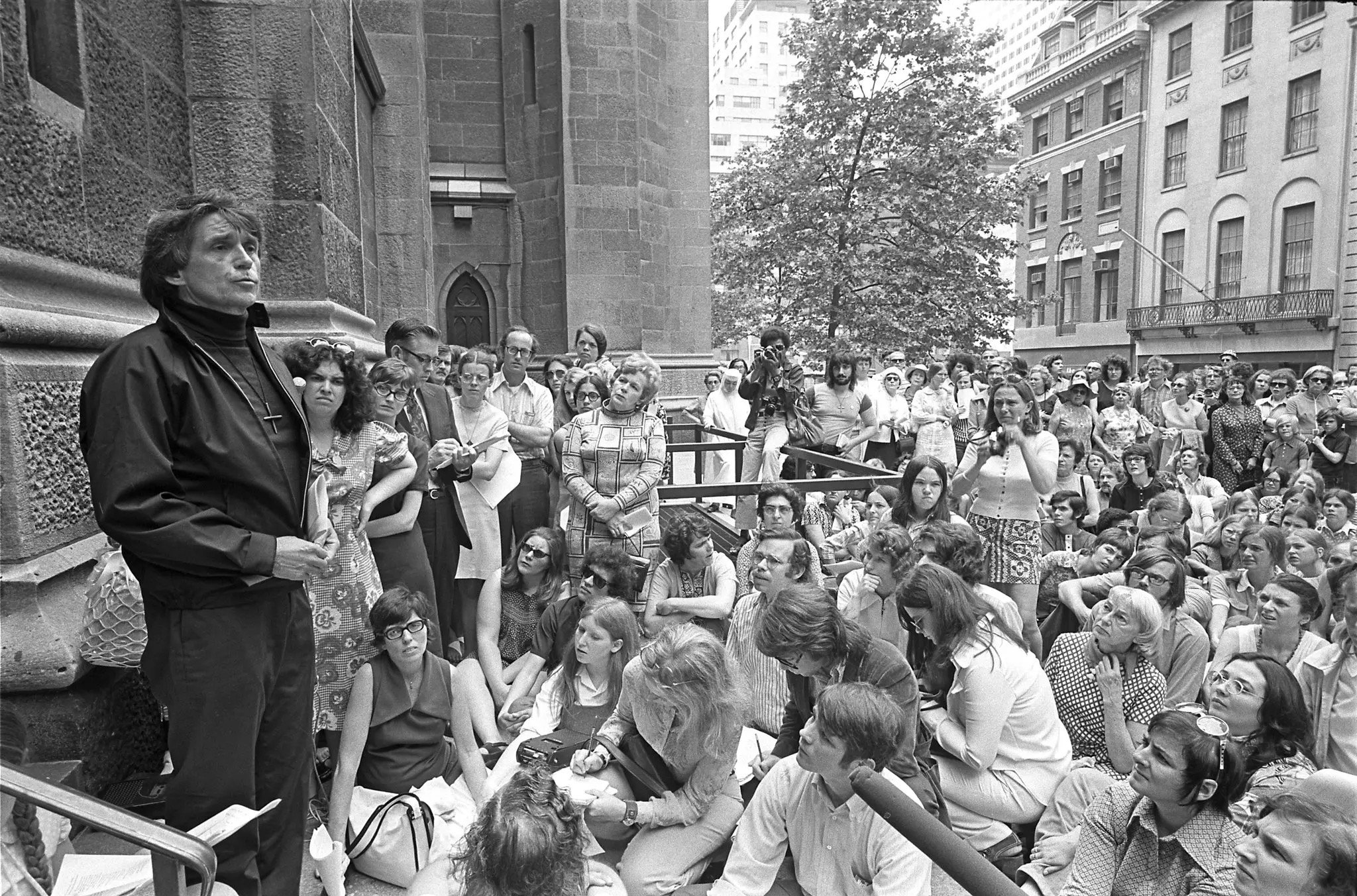

Flee: A Homily from Daniel Berrigan, S.J.

“So when you see standing in the holy place ‘the abomination that causes desolation,’ spoken of through the prophet Daniel—let the reader understand—then let those who are in Judea flee to the mountains.” (Mt 24:15-16)

There is a disturbing consonance between the long discourse of Jesus in Matthew on the final days (Matthew 24) and the Babylon passage in Revelation (Revelations 18). It is as though Jesus, sensing that His time had come, sensed also that His fate was joined irrevocably to the fate of others. Not only He was going under, gods do not die alone. Their fate convulses community and nature; their death opens a fault in the earth.

When you see the "abomination of desolation" spoken of by the prophet Daniel, standing in the holy place, "let those who are in Judea flee to the mountains." The admonition signals a final clash between the holy and the demonic. And in Revelation, under the stress of a different crisis, a parallel action is urged. "Come out of here [Babylon], my people, lest you take part in her sins, lest you share in her plagues; for her sins are heaped high as heaven, and God has remembered her iniquities."

In Revelation, certain events precipitate the advice to "flee." The Lord refers to a mysterious pollution of the temple, foreseen by the prophet Daniel, idol set up in the holy place. And in Revelation, sins and plagues seeded by the empire threaten the integrity, even the existence, of the faithful community.

There are perhaps two ways of reacting to such nightmares. The question naturally arises: Do such events as are pointed to come to pass, do the symbols "abomination of desolation" and "sins and plagues" really signal historical moments verified then and now?-do the prophecies issue in events, polluting and repressive laws, wars, blasphemies, the ousting of God from His temple?

Or are such unsettling images to be taken as mere seismic shifts, shadowy reminders of evil in the world, warnings of dangers that always remain at distance, remote evils, a darkness that invades without quenching the light of holiness?

Answers, of course, vary wondrously. There are Christians who panic at every event, wave Bibles about, coerce and shout of damnation and hellfire. They are commonly referred to as "fundamentalists," a term overlong perhaps to denote a slippage of moorings, loss of nerve, fascination with misfortune, as though God's highest activity were to foment catastrophe in nature and among His people.

But there is another way of regarding the apocalyptic and surreal passages of scripture. To certain academics, almost any scriptural truth is regarded as grist for mere mortician skills. A nightmare, a disaster, moral collapse, warning or foreboding of these-words, words are the point! Verify the word, codify it, explain its historical setting, its genesis in the cultural matrix, its influence on those times Scripture is no more than a dead letter; and this even when its words are dead serious, direly urgent, words of fury, indignation, reproach, retribution.

To the fundamentalist, the Bible is a club with which to beat the underbrush of the world, to scare up a prey: sinners, backsliders, nonbelievers, the unwary and unwashed. To some academics, the word of God is literally weightless. It comes to ground nowhere in this world, nowhere in time—with the exception, of course, of its meaning to the generation that it. But Revelation or Matthew, speaking directly to our situation, our political impasse? Absurd. No contemporary horror or crime could cause the word to start to life, to become incendiary, dangerous, to say here and now: "judgment is here and now."

I think of the fundamentalist as a contracted conscience, scripture creating a meticulously petty mind, every contingency covered; the Bible is a set of rules, a flat-out handbook of divine invention and intervention.

And the academic conscience is infinitely expandable; the Bible is an entirely apolitical treatise, certainly great and noble literature, but an Olympian word, at a distance; by no means a call to political responsibility, or a trump of judgment sounding against crimes of high power.

If I were forced to choose (and may God grant that the issue never arise, it is a choice among spikes and barbed quills), I would lean, given the times we must cope with, toward the fundamentalist. I write "lean toward" with some deliberation. I believe that detached scholarship is a greater violation of the hope of God, the divine passion to be heard and rightly understood, the truth entrusted to the hands of the intelligent and privileged. A greater violation than the stretched passion of the clumsy and ignorant, their passion to know, to be assured, comforted, strengthened by God. A strange faith indeed, yelling incontinently in one's ears in public places! But still a faith, a sense of tragedy impending, a will to walk the world step by step with eyes open, in pilgrim combat.

I understand this excess and its failures far better than I understand the betrayal of the academic, whose method makes twentieth-century dead sea scrolls of the living word.

Indeed, to such minds, does that word come down in judgment anywhere in our lifetime? Does it penetrate the political darkness, the military strongholds, whose strongest hold is precisely our darkened souls? Does that word speak in the horrific silence of Pentagon corridors at midnight, when the ghosts walk, the ghosts of humans, the ghosts of ourselves, condemned to death in mad decisions contrived in such places?

I write these words at a prestigious seminary in California, a clotting of minds and books and youth and prestige and purported scriptural savvy. Some of us have been appalled at recent government events, heavy clouds scudding the sky and darkening the noon; the thunder and veiled lightnings of nuclear intervention, the inhuman dragnet of the draft. Some of us, I say. For many others, it is theological business as usual, even while the world shudders with premonitions of disaster and the heart fails in its course. Theology as usual: the conscience as infinitely expandable, a gas filling a void with its own soporific. More than one renowned divine has been heard to mutter at the "unseemly intrusions of politics into theology."

So be it. On Ash Wednesday we urged a moratorium on classes, a vigil, prayer, a teach-in, a march, and a nonviolent sit-in at the offices of the university officials nearby. For it seems to us beyond doubt that they are conspiring in high crime, through aiding the development of nuclear weaponry at Livermore and Los Alamos death factories.

The texts of Matthew and Revelation urge the faithful to flee. The actions we engage in, whether legal or outside the law, are our way of fleeing the abomination, the crime. We choose, as nuclear apocalypse nears, to contract our conscience, to concentrate its light on a sin that heaps darkness upon darkness.

We have had enough of weightless scholarship. It floated above our heads during the Vietnam years, so nearly out of sight as to be all but invisible to the searching mind, the conscientious heart.

A kind of absurd consistency here. First Vietnam, now the nukes. And theology sails regally on, a doomed voyage; good housekeeping in a madhouse. Neglecting, ignoring the true intent of its study; the searching of scripture and a tradition of faith to lay the sword of God's judgment against human folly.

Flee the crime.

I ponder this command. There are refugees, hostages, prisoners of conscience everywhere in the world, their numbers multiplied beyond counting. Refugees fleeing crimes, war, disruption of lives. Hostages, captives of violent regimes, women and men paying the price of their service to imperial malpractice. And prisoners in every pocket of the globe, dying in gulags and ghettoes, haled before kangaroo courts, under torture and duress of every kind.

These are the ones to attend to, one eye on our text.

Meantime, what are we to do, who are at large (though ourselves hostages to nuclear terror)?

The question arose time and again during the Vietnam years. It will never cease to arise in our lifetime. To me, the question gives shape and form, even coherence, to life itself. What indeed are we to do with our lives in such mad times?

I conjure up the faces of seminarians, the wary and venturesome, the thoughtful and immature, the newborn and well-tested. A question in every eye: How are we to live? To them, I said again and again: "the future will be different if we make the present different."

Bonhoeffer's formula: "to live for the coming generation," makes sense only if we are setting about the task of the present generation. There will be no sane or peaceable future unless we are creating here and now a sane and peaceable present; in the very jaws of Leviathan.